Have Questions? Contact Us.

Since its inception, NYCLA has been at the forefront of most legal debates in the country. We have provided legal education for more than 40 years.

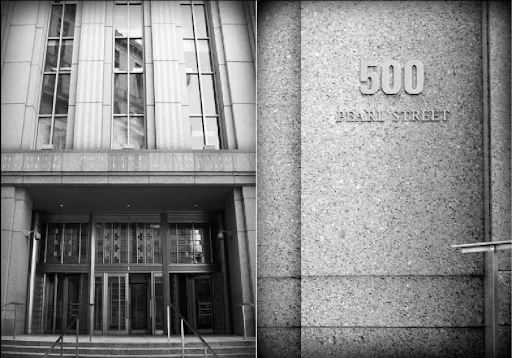

The United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York:

A Retrospective (2000-2010)

New York County Lawyers’ Association

Committee on the Federal Courts

May 2012

Copyright May 2012

New York County Lawyers’ Association

14 Vesey Street, New York, NY 10007

phone: (212) 267-6646

Additional copies may be obtained on-line at the NYCLA website

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | |

| INTRODUCTION | |

| A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COURT | |

| THE EDWARD WEINFELD AWARD | |

| CHIEF JUDGES: TRANSITION AND CONTINUITY | |

| JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS: THE MAKING OF A NEW COURT | |

| MAGISTRATE JUDGES: INCREASED ROLE AND INFLUENCE | |

| THE COURT’S CHANGING DOCKET | |

| NOTABLE CASES, TRIALS, AND DECISIONS | |

| Antitrust | |

| Civil Rights | |

| Class Action Litigation | |

| Commercial Law | |

| Criminal Law | |

| E-Discovery | |

| Environmental | |

| First Amendment | |

| Intellectual Property | |

| International Law | |

| Internet Law | |

| Securities Litigation | |

| Terrorism | |

| IN MEMORIAM | |

| MEMBERS OF THE NEW YORK COUNTY LAWYERS’ ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE ON THE FEDERAL COURTS | |

| APPENDIX | |

| Chief Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (2000 to 2010) | |

| Active Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York | |

| Senior Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York | |

| Magistrate Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York | |

| Former Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (2000 to 2010) | |

| Former Magistrate Judges of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (2000 to 2010) | |

The courts are what the judges make them, and the District Court in New York, from the time of [District Judge] James Duane, [President] Washington’s first appointment, has had a special distinction by reason of the outstanding abilities of the men [and women] who have been called to its service.

Hon. Charles Evans Hughes, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, November 3, 1939.

As Chief Justice Hughes aptly observed, though the Southern District through its age and location has invited some of the most complex and important cases, its unparalleled distinction has arisen from the exceptional judges who have guided the hand of justice. A total of 139 judges have served on the Southern District bench since its founding in 1789. Although more than a few of these judges— Samuel R. Betts, Charles M. Hough, Learned Hand, and Edward Weinfeld—are widely regarded as among the finest jurists of their (or any) time, the Southern District did not gain and has not maintained its well-deserved reputation on the coattails of only a few notable names.

The Southern District always has been and today remains a court of dedicated and skilled jurists who distinguish themselves daily by their workmanlike approach to the business of the federal district court: hearing and deciding cases, great and small. In this way, the judges of the Southern District carry on in the tradition of Judge Weinfeld who famously advised that “every case is important” and “no case is more important than any other case.”

The “Mother Court,” as the Southern District is colloquially known, is the oldest federal court in the United States, pre-dating by several weeks the organization of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Judge Duane received his commission from President George Washington on September 26, 1789, the same day the President signed the commission for John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the United States. As difficult as it is for those of us familiar with the busy workload of the modern court to believe, for the first several years of its existence, Judge Duane presided over a court that quite literally “had nothing to do.”

Indeed, the court’s first case, United States of America v. Three Boxes of Ironmongery, Etc., an application by the fledgling government of the United States for a declaration that certain goods were subject to duty, was not filed until April 1790. As its first case suggests, the court’s early years were consumed by customs cases and routine or uncontested admiralty matters. As Judge Thomas D. Thacher, who served on the Southern District bench in the late 1920s, once remarked: “The work of such a court must have been extremely dull.”

In 1812, Congress created a second judgeship in the District of New York to fulfill a statutory requirement that the court hold proceedings upstate.10 Less than two years later, on April 9, 1814, Congress passed a statute bisecting the District of New York, giving birth to the Southern District of New York. In 1821, the Southern District promulgated for the first time, with the assistance of a committee of bar leaders, a set of procedural rules governing cases brought in the court.

On December 21, 1826, Judge Samuel R. Betts was appointed to the Southern District bench.13 Judge Betts served on the court for 41 years until his death in 1867, during which time he oversaw dramatic change. An authority on admiralty law, he presided over the court during a period when maritime cases “multiplied many times in volume and importance” and singlehandedly transformed the Southern District from a court that “had nothing to do” into a “busy tribunal.”16 Holding office during the Civil War era, Judge Betts presided over important cases involving “questions of prize, blockade and contraband resulting from captures of enemy property by U.S. vessels in the blockade of Confederate ports.”

Congress created the Eastern District of New York in 1865. This move helped to reduce the Southern District’s burgeoning workload and forestalled for nearly 40 years the creation of a second judgeship on the Southern District bench. The avalanche of filings occasioned by the passage of the Bankruptcy Act of 1898, however, prompted Congress to create a second judgeship for the court in 1903. Indeed, in 1900, for example, bankruptcy filings exceeded the total of all other cases brought in the Southern District during that year.

In 1906, a third Southern District judgeship was created, followed by a fourth in 1909. To these posts President Theodore Roosevelt appointed two of the nation’s finest jurists: Judges Charles M. Hough and Learned Hand. Both men served on the Southern District bench for extended terms, ten years for Judge Hough and 15 years for Judge Hand, before he was elevated to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

During the first few decades of the twentieth century, the Southern District experienced tremendous growth in both the volume and the variety of its caseload. According to Paul Burak’s History, the growth was caused by “private litigation in diversity of citizenship [that] increased due to the rapid development of commerce in New York, and government litigation [that] similarly multiplied with the extension of federal control over many private and public activities.” Indeed, the Southern District faced a total of 9,123 new filings in 1920, more than three times the number of filings that were made just ten years earlier in 1910. From 1920 to 1930, the court’s workload grew heavier still when the onset of Prohibition in 1920 caused “a staggering increase in government civil business, such as actions for tax or penalty, forfeitures, and ‘padlock’ cases, and an even greater rise in criminal liquor cases.”

On November 3, 1939, the 12 judges of the Southern District paused from their labors to commemorate the court’s sesquicentennial anniversary with a ceremony presided over by Chief Judge John Clark Knox. Although Judge Knox spoke about the Southern District as it was over 70 years ago, his words still ring true today:

Along with the Government, the court has grown in power, influence and importance. Indeed, it presently exercises a jurisdiction that, perhaps, is wider than that of any tribunal upon the earth …. In times of peace and days of war, in years of plenty and periods of want, this court—modestly and unostentatiously—has endeavored faithfully to perform duties which these conditions imposed upon it …. We indulge the hope that, in the future, quite as much as it has done in the past, the court will creditably do its work and fairly administer justice to all who come within its portals …. We also trust that as long as the Government stands, and may that be forever, this court will be a place to which all men in need of judicial aid may freely come and have confidence that justice will here be dispensed without favor and without price.

The distinguished jurists of the day who observed the ceremony uniformly praised the quality and dedication of the judges who had served on the Southern District bench. In addition to Chief Justice Knox’s words and Chief Justice Hughes’s statement quoted at the beginning of this section, Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter praised the court’s “great tradition of eminent judges of the highest standard of judicial administration.”

Judge Knox also used the occasion of the court’s birthday to press the case that additional judges were needed to handle the Southern District’s expanding caseload, noting in his speech that “there is no more heavily burdened court than this District Court whose anniversary we celebrate.” During the early 1940s, the Southern District’s pending civil docket ranged between 3,500 and 4,500 cases per year. This figure skyrocketed to more than 10,000 cases in 1947, even though the court disposed of 4,708 cases in that year alone. Congress finally responded with additional judgeships in 1949 when four were added, bringing the court to 16 judges.

In 1950, President Harry S. Truman appointed the 49-year-old President of the National Public Housing Conference and former New York City Public Housing Commissioner, Edward Weinfeld, to the court. Judge Weinfeld, widely noted as the greatest judge ever to sit on the Southern District bench and, to many, the greatest judge ever to sit on any district court, did more than any judge before him or since to set the tone and work ethic for the court he called “the greatest in the country, bar none.” For many of his 38 years on the court, Judge Weinfeld regularly arrived at the courthouse before 6 a.m. to begin 12- hour working days for six or seven days a week, including most holidays. Judge Weinfeld famously reflected on his attitude towards his vocation:

When, at a fairly early hour of the morning, I put the key into the door of my darkened chambers and walk across the room to start the day’s activities, I do so with the same enthusiasm that was mine the very first day of my judicial career. What one enjoys is not work. It is joy.

Because of his work ethic and talent, Judge Weinfeld, from his earliest days on the court to the twilight of his judicial career, set an example to which his colleagues and the others who knew him aspired. The more than 2,200 published opinions he authored during his 38-year career are hailed as “well-crafted,” “thoroughly grounded in the facts,” and “products of reason rather than acts of will.”38 Given those qualities, encouragingly, they were “almost always affirmed.” Similarly, as two of his law clerks observed, “[I]t is difficult, if not impossible, to capture the reality of the dignity and fairness that are the hallmarks of a Weinfeld trial … [in which he brings] to life that which is finest in our legal tradition.”

It would be difficult to overstate Judge Weinfeld’s influence on the judges who have served, and who now serve, on the Southern District bench. In 1985, the judges of the Southern District shared that sentiment in a letter to the selection committee for the nomination of Judge Weinfeld for the Devitt Distinguished Service to Justice Award:

Judge Weinfeld has been a friend, a colleague, and a mentor for us and for other judges on this Court for the past thirty-five years. In that time, no one has labored as long or as hard in the service of justice as has Judge Weinfeld. While his contributions to the administration of justice have been great on many levels, the greatest is the personal example he has set for all those who know him or know of him. . . . Judge Weinfeld has set the standard for the conduct of judges, attorneys, and all others connected with the administration of justice. And he has set that standard not simply by what he has said or written, but rather by the daily devotion he has shown, year after year, to the rule of law.

Following a long illness, during which he continued to conduct trials and decide cases, Judge Weinfeld died in January 1988. Although Judge Weinfeld’s death undoubtedly marked the end of an era for the Southern District, he is survived by the personal example and standards he set for the judges who served with him and after him. In this way, the Southern District today remains a court of talented and hard-working judges who continue, in the tradition of Judge Weinfeld and the scores of other judges who served before him on the court, to distinguish themselves daily through their work ethic and dedication to the business of the federal district court—hearing and deciding cases, great and small.

The New York County Lawyers’ Association’s Committee on the Federal Courts established the Edward Weinfeld Award to honor those who have made distinguished contributions to the administration of justice, in the tradition of Judge Weinfeld.

The following members of the New York legal community have been honored with the Edward Weinfeld Award:

| Hon. James L. Oakes | 1992 |

| Hon. Leonard B. Sand | 1993 |

| Hon. Morris E. Lasker | 1994 |

| Hon. Wilfred Feinberg | 1995 |

| Hon. John S. Martin | 1996 |

| Hon. Jon O. Newman | 1997 |

| Mary Jo White, Esq. | 1998 |

| Hon. Eugene Nickerson | 1999 |

| Hon. Joseph McLaughlin | 2000 |

| Hon. Loretta Preska | 2001 |

| Hon. Edward Korman | 2002 |

| Hon. Allen Schwartz | 2003 |

| Hon. Jack Weinstein | 2004 |

| Hon. Shira Scheindlin | 2005 |

| Hon. Charles L. Brieant | 2006 |

| Hon. Pierre Leval | 2007 |

| Hon. John Gleeson | 2008 |

| Hon. Gerard Lynch | 2009 |

| Hon. Denny Chin | 2010 |

| Hon. John F. Keenan | 2011 |

The position of Chief Judge in the Southern District is given to the most senior active judge in the district who is not yet 65 years old. The position is held for seven years or until its holder turns 70. The duties of the Chief Judge include managing the work of the active and senior judges and the magistrate judges, as well as managing the court clerk’s office, probation, pretrial services, court reporters, and security. In addition, the Chief Judge is the Southern District’s representative to bar groups, national court committees, and other branches of the government.

The Hon. Michael B. Mukasey served as Chief Judge from 2000 through 2006. He had to deal with heightened security concerns at the court and with the need to implement necessary security precautions. Chief Judge Mukasey, along with Chief Judge John M. Walker of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, was involved in efforts to renovate the courthouse at 40 Foley Square, which in addition to housing judges and court personnel from the Southern District, also houses Second Circuit judges’ chambers and courtrooms. The 40 Foley Square courthouse, designed by Cass Gilbert, has been referred to by Chief Judge Mukasey as “a treasure of American architecture.” It was renamed the Thurgood Marshall Courthouse in 2003 after the late Supreme Court justice and former U.S. Court of Appeals Judge for the Second Circuit. Since renovations began to the Thurgood Marshall Courthouse in 2006, both the Southern District and the Second Circuit have operated in the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse.

The Hon. Kimba M. Wood succeeded Chief Judge Mukasey in 2006 and served in that capacity until she took senior status in 2009. The Hon. Loretta A. Preska, the current Chief Judge and a former member of NYCLA’s Committee on the Federal Courts, assumed the reins in 2009.

The court enjoyed substantial growth in the number of judgeships between 1990 and 2000, rising from 38 judges to 50, but that number had retracted to 38 at the start of 2011 before Congress confirmed outstanding appointments to bring the total to 44 by 2012. However, similar to other districts during the tail end of the 2000s, the Southern District in 2012 had five judicial vacancies awaiting confirmation of presidential nomination. Unlike the decade between 1990 and 2000, when more than 20 new judges were appointed to the bench, between 2000 and 2010 only nine new judges were appointed (compared to eight in 1994 alone). Of the 38 judges who sat on the court in the beginning of 2011, 22 were active and 16 were senior, as the court continued to rely upon senior judges to manage its ever-rising caseload.

Of the judges who served in the Southern District between 2000 and 2010, several were historic firsts on the federal bench, including the Hon. Constance Baker Motley (the first African-American woman to serve on the federal bench and the first woman to serve as judge of the Southern District), the Hon. Denny Chin (the first Asian-American appointed as a U.S. district judge outside of the Ninth Circuit and the only Asian-American judge in active service in the federal appellate court system at the beginning of 2011), and the Hon. Deborah A. Batts (the first openly gay person to serve on the federal bench).

In the Southern District, there are 15 magistrate judges. This is an increase from 14 in 2000 and an increase from nine full-time magistrates in 1990. Magistrate judges are not Article III judges; therefore, they are not appointed by the President and they do not have life tenure. Rather, they are appointed by the local district judges, and full-time magistrate judges serve eight-year terms. Whereas the earliest magistrate judges handled only pretrial discovery matters, today they are much more involved in all aspects of litigation and in the Southern District often play a key role in assisting the district judges in moving cases along swiftly.

There has been considerable litigation over the role of magistrate judges in criminal matters. As a result of such litigation, the range of functions performed by magistrate judges in criminal cases has expanded, though gradually. Whereas magistrate judges were once given discretion almost exclusively in “pretrial” matters, in the 1990s they were given considerably more authority to become deeply involved in substantive matters. This trend continues today.

In civil cases, magistrate judges generally are empowered to make three types of decisions. First, they can issue interlocutory orders, which a district judge can then review, as if on appeal. Second, magistrate judges can issue a “report and recommendation” on a case-dispositive motion; these are reviewable de novo by the district judge, but often, as a practical matter, may greatly influence the district judge’s ultimate ruling. Finally, with the consent of all parties, magistrate judges can preside over civil trials and bring cases to final judgment, with review available only in the Court of Appeals.

Magistrate judges on the Southern District have also been at the forefront of the developing case law concerning E-Discovery. For example, Judge Frank Maas in Aguilar v. Immigration & Enforcement Div. of U.S. Dept. of Homeland Sec., 255 F.R.D. 350 (S.D.N.Y. 2008), provided a primer on the various types of metadata associated with the many different types of electronic data files and an analysis of the considerations relevant to the discovery of such metadata. Judge Maas also teaches federal judges about E-Discovery for the Federal Judicial Center. Judge Andrew Peck in William A. Gross Constr. Assocs., Inc. v. American Mfgs. Mut. Ins. Co., 256 F.R.D. 134 (S.D.N.Y. 2009), issued a “wake-up call to the Bar” on their obligations to cooperate with opposing counsel in formulating “keywords” for searches of electronic data files. Judge Peck (along with Judge Scheindlin) is a member of the Advisory Board of the Sedona Conference, a nonprofit legal research and educational organization dedicated to resolving E- Discovery issues. The Sedona Principles and the Sedona Conference Cooperation Proclamation have been endorsed by courts throughout the country.

The workload of the court increased steadily from 2000 to 2010. A total of 11,547 cases (10,389 civil and 1,158 criminal) were filed in the Southern District in 2000, and 14,275 cases were pending at the end of that year. In 2009, 11,909 cases (10,883 civil and 1,026 criminal) were filed in the court, but 26,320 cases were still pending as of March 31, 2010. Dividing this workload by the 40 judges (26 active, 14 senior) on the court at the time yields an average of 658 pending cases per judge or 1,012 pending cases per active judge in 2010.

The workload of judges in the Southern District exceeds the workloads of district judges serving in other major metropolitan areas. For example, in 2010, there were 9,642 pending cases in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. That year, the Northern District of Illinois had a total of 33 judges, of whom 19 were active and 14 senior, yielding an average of 292 pending cases per judge or 507 cases per active judge. The Central District of California had 12,415 pending cases in 2010, which were handled by a total of 35 judges, of whom 26 were active and nine senior. This yields an average of 355 cases per judge or 478 cases per active judge.

There were also significant changes in the composition of the Southern District’s civil and criminal dockets during this period. Several categories of civil cases experienced dramatic increases in filings from 2000 to 2009: labor suits (54% increase); torts (15% increase); real property (14% increase); and civil rights (13% increase). By contrast, civil cases in the following areas showed substantial decreases in filings: social security (44% decrease); forfeiture and penalties and tax suits (43% decrease); prisoner petitions (25% decrease); and copyright, patent and trademark (13% decrease). Other civil case categories stayed relatively constant during this period: contracts (6% increase) and all other civil cases (7% decrease).

As noted, criminal case filings rose significantly from 1,158 filings in 2000 to 1,404 filings in 2009, or a 21% increase. The largest increases were seen in the following criminal case categories: robbery (200% increase); and immigration (99% increase). Significant decreases were observed in the following categories: embezzlement (70% decrease); forgery and counterfeiting (42% decrease); fraud (40% decrease); burglary and larceny (15% decrease); firearms and explosives (14% decrease); and all other criminal felonies (10% decrease). There were no significant changes in the remaining criminal case categories: drugs (2% decrease); and homicide and assault (8% decrease).

As has been the case throughout the court’s long history, Southern District judges during the 2000s weighed in on some of the most pressing legal issues of the day, rendering numerous path- breaking decisions and presiding over a series of important trials. Members of the Report Subcommittee sought to identify an illustrative sampling of notable cases, trials, and decisions, which are discussed below. Of course, many other notable cases, trials, and decisions came out of the court during the 2000s, but due to space constraints this Report is able to refer to only a small fraction of them.

Discover Fin. Servs., LLC v. Visa U.S.A. Inc.

In Discover Fin. Servs., LLC v. Visa U.S.A. Inc., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 65627 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 26, 2008), Judge Barbara S. Jones denied defendants’ motion for summary judgment in an antitrust case brought by credit card issuer Discover Financial Services, DFS Services, LLC, and Discover Bank (“Discover”) against Visa U.S.A. Inc. and Visa International Service Association (“Visa”) and MasterCard Incorporated and MasterCard International Incorporated (“MasterCard”). Discover sought damages from Visa and MasterCard for enacting exclusionary rules preventing Visa and MasterCard member banks from issuing Discover Cards. The rules, Discover argued, derailed Discover’s joint venture with Citibank to combine Discover’s network with Citibank’s Diners network, with Citibank moving over its issuing volumes of credit cards to the combined network (“Project Explorer”). Visa and MasterCard filed a summary judgment motion seeking to preclude Discover from recovering damages attributed to the failure of Project Explorer.

Visa and MasterCard argued that there was insufficient evidence to find that the exclusionary rules were an essential element that led to the failure of Project Explorer. Further, Visa and MasterCard argued that the Tenth Circuit had previously found that an analogous exclusionary bylaw did not violate the Sherman Act. Thus, even if the failure of Project Explorer could be attributed to the exclusionary rules, the failure would result from lawful conduct.

Judge Jones denied the motion for summary judgment, relying on the testimony of several Discover executives attributing the failure of Project Explorer to the exclusionary rules. The court opined that even if the statements of Discover’s executives were self-serving, the statements were made “well before the filing of this private action.” Id. at *14. Furthermore, there was “testimony from Citibank executives that the exclusionary rules were a serious consideration during the Project Explorer negotiations ….” Id. at *13. Therefore, Judge Jones noted that, although the evidence was thin, it was sufficient to withstand summary judgment when viewed in the light most favorable to Discover.

The Court also dismissed the defendants’ reliance on a Tenth Circuit decision, SCFC ILC, Inc. v. Visa USA, Inc., 36 F.3d 958 (10th Cir. 1994), as inapplicable because that decision was based on Visa’s procompetitive justification. In that case, the justification for the analogous bylaw was that it was designed to prevent competitors from freeloading off a system that the competitors had done nothing to create—a justification that did not apply in the case before Judge Jones.

The case subsequently settled.

In Re: IPO Antitrust Litig.

In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an antitrust ruling of Judge William H. Pauley III of the Southern District, reinstating the District Court’s dismissal of an action that had been reversed by the Second Circuit. In doing so, the Court ruled that there was implied preclusion of antitrust laws where securities laws and antitrust laws are incompatible.

In January 2002, 60 investors filed two antitrust class-action lawsuits against ten leading investment banks, seeking relief under, among other things, Section 1 of the Sherman Act, the Robinson- Patman Act, and state antitrust laws. The investors alleged that “between March 1997 and December 2000 the banks had acted as underwriters, forming syndicates that helped execute the initial public offerings (IPOs) of several hundred” companies, mostly technology-related. Credit Suisse Secs. (USA) LLC v. Billing, 551 U.S. 264, 269 (2007.) The complaints alleged that the underwriters “abused the … practice of combining into underwriting syndicates” by “agreeing among themselves to impose harmful conditions upon potential investors—conditions that the investors apparently were willing to accept in order to obtain an allocation of new shares that were in high demand.” Id. (describing complaints; internal quotation omitted). In particular, the complaints alleged that investors were forced to pay anticompetitive charges over and above the agreed IPO share price plus the underwriting commission. Id. at 269-70. The complaints “added that the underwriters’ agreements to engage in some or all of these practices artificially inflated the share prices of the securities in question.” Id. at 270.

The District Court dismissed the complaints, finding the conduct alleged by the plaintiffs to be impliedly immune from antitrust laws, acknowledging that “the SEC, the NASD, and other SROs will continue to study the conduct alleged.” In re Initial Public Offering Antitrust Litig., 287 F. Supp. 2d 497, 524-25 (S.D.N.Y. 2003). The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit vacated and remanded, however, finding that there was no implied preclusion of the antitrust laws. Billings v. Credit Suisse Sec. (USA) LLC, 426 F.3d 130, 170, 172 (2d Cir. 2005). The Supreme Court, in turn, reversed the Second Circuit. Credit Suisse, 551 U.S. at 264. The Court observed that, when “decid[ing] whether securities law precludes antitrust law, it is deciding whether … the two are ‘clearly incompatible.’” Id. at 275. A court will find incompatibility where: (i) a regulatory authority exists under the securities law to supervise the activities at issue, (ii) there is evidence that authority is exercised, (iii) there is a risk that application of both securities and antitrust laws would produce conflicting requirements or standards, and (iv) the conflict would affect practices that lie “squarely within the heartland of securities regulations” (such as financial market activity) that are subject to “active and ongoing” regulation by the appropriate federal authority. Id. at 275, 285. Applying this standard, the Court concluded that the securities laws precluded the plaintiffs’ antitrust claims because, inter alia, (i) the challenged conduct—the defendants’ alleged activities in connection with the sale of newly-issued securities—was adequately regulated; and (ii) a serious conflict existed between the antitrust and securities regulatory regimes, such that application of the antitrust laws would pose “substantial risk of injury to the securities market.” Id. at 284-85.

Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld in 2007 a ruling of Judge Gerard E. Lynch (then a Southern District judge) dismissing an antitrust action, reversing a Second Circuit decision that had overturned Judge Lynch—and clarified the pleading standard a plaintiff must meet to withstand a motion to dismiss.

In Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, the plaintiffs brought a class-action lawsuit alleging that Bell Atlantic and a number of other large communications companies had engaged in anticompetitive behavior in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act. Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 554 (2007). Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants had disadvantaged smaller telephone companies and overcharged consumers by refraining from entering markets where another large company was dominant (thereby preventing price competition). The complaint focused on parallel conduct and did not allege direct evidence of concerted activity. Judge Lynch dismissed the complaint, holding that it had not alleged sufficient facts to state a claim for a violation of the Sherman Act. Twombly, 313 F.Supp.2d 174, 179 (S.D.N.Y. 2003). Specifically, the allegations of parallel business conduct, taken alone, did not state a claim; a complaint must allege additional facts that “ten[d] to exclude independent self-interested conduct as an explanation for defendants’ parallel behavior.” Id. at 179. The District Court found that plaintiffs’ allegations of parallel actions to discourage competition were inadequate because “the behavior of each [large telephone company] in resisting the incursion of [smaller telephone companies] is fully explained by the [large company’s] own interests in defending its individual territory.” Id. at 183. As to the defendants’ supposed agreement against competing with each other, the District Court found that the complaint had “not alleged facts … suggesting that refraining from competing in other territories as the small telephone companies was contrary to [the large companies’] apparent economic interests, and consequently [had] not raised an inference that [the large companies’] actions were the result of a conspiracy.” Id. at 188.

The Second Circuit vacated and remanded the Southern District decision, applying a lower pleading standard. The Second Circuit held that the plaintiffs were not required to plead “facts in addition to parallelism to support an inference of collusion” for an antitrust claim based on parallel conduct to survive a motion to dismiss. Twombly, 425 F.3d 99, 114 (2d Cir. 2005).

The Supreme Court, in turn, reversed the Second Circuit, agreeing that Judge Lynch’s dismissal of the claim was appropriate. Twombly, 550 U.S. at 564. As an initial matter, the Supreme Court clarified the requirements of proving a claim of anti-competitive behavior under Section 1 of the Sherman Act. The Court held that while parallel conduct—actions by competing companies that might be seen as implying some agreement to work together—is “admissible circumstantial evidence” from which an agreement to engage in anti-competitive behavior may be inferred, parallel conduct alone is insufficient to establish a Sherman Act claim. Id. at 555-54. As such, the Court found that the allegations of the complaint, largely based on allegations of parallel conduct, failed to meet this standard.

The Supreme Court’s decision is most often cited for its enunciation of a new pleading standard under Fed. R. Civ. P. 8. The Court opined that a plaintiff must come forward with factual allegations that are “plausible” enough to raise a right to relief above the “speculative level” on the assumption that all of the complaint’s allegations are true. Id. at 555. (“[A] plaintiff’s obligation to provide the grounds of his entitlement to relief requires more than labels and conclusions, and a formulaic recitation of the elements … will not do.”). The Court reasoned that asking for plausible grounds does not impose a “probability requirement at the pleading stage” and simply calls for enough facts to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence of illegal agreement. Id. at 556. The Court held that because the plaintiffs had not “nudged their claims across the line from conceivable to plausible,” their complaint must be dismissed. Id. at 570.

Doe v. Vill. of Mamaroneck

In Doe v. Vill. of Mamaroneck, 462 F. Supp. 2d 520 (S.D.N.Y. 2006), Judge Colleen McMahon found that the Village of Mamaroneck, New York (the “Village”) had discriminatorily enforced its laws and thus had violated the Equal Protection Clause. Day laborers of Latino descent had sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleging that the Village implemented a “campaign of harassment and intimidation” against the day laborers. Id. at 526. The complaint alleged that the Village engaged in discriminatory law enforcement activities targeted at the day laborers even though no records indicated any complaints implicating day laborers in any criminal activity. Id. at 531. The Village indefinitely barred day laborers from gathering at a park where they had customarily gathered. As a result of such measures, the hiring of day laborers in Mamaroneck almost completely halted.

In finding in favor of the plaintiffs, Judge McMahon reasoned that, while the laws to reduce the number of day laborers were facially neutral, the laws were discriminatorily applied. She concluded that the increase in police activity was designed to harass the day laborers and that the harassment “was tinged with racism.” Id. at 552. Judge McMahon found that the Village’s proffered justification failed because no correlation was shown between the day laborers and increased crime or degraded quality of life. However, Judge McMahon found that plaintiffs’ “selective enforcement” claim failed since the plaintiffs could not demonstrate that a “similarly situated” group was treated more favorably. Id. at 544-59.

Finch v. New York State Office of Children and Family Services

New York, like most states, maintains a registry that lists the names of people who have been accused of child abuse where an investigation has revealed evidence to support such an allegation. Adding a name to the registry is easily done, but the consequence of such inclusion can be economically devastating and far-reaching. Before an employer who is engaged in childcare may hire an applicant, the law requires that an inquiry be made to ascertain whether the job applicant is listed on the registry. If the applicant is not listed, the employer receives a “no hit” letter. If listed, a “hit letter” is sent to the employer, effectively foreclosing any opportunity for the applicant to be gainfully employed in the childcare industry. A name can remain on the registry for up to 28 years.

In 1994, the Second Circuit in Valmonte v. Bane, 18 F.3d 992 (2d Cir. 1994), held that the legal requirement that employers consult the registry is a government-created impediment to employment that infringes upon the constitutionally protected liberty interest to pursue one’s vocation of choice. Valmonte required there must be a due process hearing before a listing is disclosed to a prospective employer. Left undecided was the time in which such due process hearing must take place. Finch v. New York State Office of Children and Family Services, filed in February of 2004, challenged the substantial delays in scheduling these hearings. As a result of the Valmonte decision, the State did not respond at all to a clearance request when a hearing was pending. Since hearings took years to complete, many people who were awaiting a clearance lost job opportunities even though 60-70% of the people who eventually received their hearings were exonerated.

Judge Shira Scheindlin certified a plaintiffs’ class in Finch. 252 F.R.D. 192 (Aug. 11, 2008). After denying the State’s motions to dismiss (at 499 F. Supp. 2d 521 (July 3, 2007)), and for summary judgment (No. 04 Civ. 1668, 2008 WL 5330616 (Dec. 18, 2008)), the trial was scheduled to begin in

March of 2010.

Before the trial was set to start, a worker at the State Central Registry informed counsel that, after the litigation was filed, certain projects were undertaken that resulted in the wrongful termination of hearing requests. In an attempt to alleviate the backlog of hearings, the State contacted prospective employers who had requested information to determine if those employers were still interested in the job applicant. However, because these calls happened years after a clearance request was made, the employers were typically no longer interested in the applicant. Upon so determining, the State closed the request for a hearing, noting the hearing had been waived. Once marked as “waived,” the job applicant and subject of the clearance was permanently foreclosed from receiving a hearing in the future. These actions violated the intent of the statutory scheme that created the registry—that the job applicant has a right to a hearing, not the inquiring employer. See N.Y. Soc. Serv. § 422 et seq. After discovery confirmed the “whistleblower’s” allegations, the State agreed to settle the claims. Beginning in August 2010, and staggered over 15 months, notices were to be sent to 20,000 people whose hearings were terminated by these projects. The notice advised the class members of their right to reopen their waived hearings. As a result of the settlement, over 1,000 New Yorkers have requested their hearings to be reopened.

As the partial settlement related only to the hearing-termination projects, the question as to how long it should take to complete hearings remained outstanding. The trial to settle that issue was scheduled to start in September 2010 but, on the eve of trial, the parties reached a final settlement. For those whose opportunity to work was impeded, hearings were to be completed in four months. For those whose jobs were not immediately at risk, hearings were to be completed in eight months. Compliance with these time limits was to be monitored by appointed class counsel for up to three years.

McBean v. The City of New York

On October 4, 2007, New York City’s Department of Corrections admitted that, since 2002, approximately 150,000 pretrial detainees arraigned on misdemeanors and lesser offenses were illegally strip-searched at admission, even though there was no reason to believe they were concealing drugs or contraband. These strip searches required groups of detainees to fully undress in front of each other and in front of multiple guards, lift their genitals or breasts, spread their buttocks, cough while squatting, and allow guards to inspect their private body cavities. The City admitted that these illegal strip searches had been continuing, despite sworn statements to the court in December 2002 that these strip searches had stopped and despite a 2001 Second Circuit decision, Shain v. Ellison, 273 F.3d 56, 65 (2d Cir. 2001), which held that it had been “clearly established” since at least 1995 that these strip searches were prohibited by the Fourth Amendment.

In a settlement approved by the court on October 21, 2010 (preliminarily approved March 22, 2010), the City agreed to immediately cease strip-searching pretrial detainees charged with only non- felony offenses and to pay damages to those illegally strip searched between July 23, 2002 and October 4, 2007. The City also agreed to train all officers to ensure that these strip-search practices would not continue, to revise its policies regarding strip-search procedures, and to post signs at Department of Corrections facilities notifying detainees of their right not to be strip-searched at admission without reasonable suspicion. An independent monitor, appointed by Judge Gerard Lynch of the Southern District, will “ensure” or “supervise” the City’s compliance. New York City agreed to pay $33,000,000 in damages to approximately 100,000 pretrial detainees arraigned on misdemeanors and lesser offenses who were illegally strip-searched at admission to a City jail between 1999 and 2007.

At the time of the settlement, other cases challenging strip searches of pretrial detainees were pending in courts throughout the nation. One of those cases went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the government, holding that, in many instances, corrections officials have a right to conduct suspicionless strip searches of people who have been arrested for even minor crimes. Florence v. Board of Chosen Freeholders, 132 S. Ct. 1510 (2012). The Supreme Court’s decision does not affect the 2010 settlement in McBean.

In re Amaranth Natural Gas Commodities Litig.

In re Amaranth Natural Gas Commodities Litig., 269 F.R.D. 366 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), was a class action case where Judge Scheindlin established the standard for class certification in a case that alleged market manipulation under the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA”). In Amaranth, the plaintiffs—futures traders who sold or held natural gas futures or options on futures contracts between February 16, 2006 and September 28, 2006—brought a case alleging that the defendants manipulated prices of New York Mercantile Exchange natural gas contracts in violation of Sections 6(c), 6(d), and 9(a)(2) of the CEA.

After outlining the requirements under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a), Judge Scheindlin discussed the implied requirement of ascertainability: “[A] class will not be deemed satisfied unless the class description is sufficiently definite so that it is administratively feasible for the court to determine whether a particular individual is a member.” Id. at 376-78. The Amaranth defendants argued that the proposed class was not ascertainable for either of plaintiffs’ claims on the grounds that some of the potential class members had net short or long positions making it impracticable for the court to determine whether an individual was a class member. Id. at 381.

The court, citing Judge Richard Posner of the Seventh Circuit, outlined the requirement for ascertainability with respect to the CEA and concluded that ascertainability can be determined objectively through mechanical calculations—notwithstanding that it would require complex math to determine if a plaintiff held a net long or short position. With CEA cases it is true:

that a class will often include persons who have not been injured by the defendant’s conduct; indeed this is almost inevitable because at the outset of the case many of the members of the class may be unknown, or if they are known still the facts that bear on their claims may be unknown. Such a possibility or indeed inevitability does not preclude class certification, despite statements in some cases that it must be reasonably clear at the outset that all class members were injured by the defendant’s conduct. Those cases focus on the class definition; if the definition is so broad that it sweeps within it persons who could not have been injured by the defendant’s conduct, it is too broad.

Id. at 283 (quoting Kohen v. Pacific Inv. Mgmt. Co. LLC (“PIMCO II”), 571 F.3d 672, 677 (7th Cir. 2009)).

Judge Scheindlin also discussed the relevant time for a court to evaluate expert testimony in a CEA case, holding that at the class certification stage district courts are only permitted to resolve merits- based factual disputes that overlap with certifications. Id. at 384. Plaintiffs are not required to successfully employ their proposed methods for finding causality at the class certification stage. Id. at 385. Finally, the fact that damages must be calculated on an individual basis was no impediment to class certification. Id. The court determined that plaintiffs fulfilled the requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a) and (b) and certified the class.

In Re Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether Prod. Liab. Litig.

In In Re Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether (“MTBE”) Prod. Liab. Litig., 209 F.R.D. 323 (S.D.N.Y. 2002), private well owners sought class certification for their claims against 20 oil companies based on the alleged widespread contamination of groundwater as a result of the use of gasoline additives. Judge Scheindlin held that treating this case as a class action would “stretch the decidedly elastic class action device beyond its breaking point—causing it to snap” and denied the plaintiffs’ motions for certification. Id. at 329.

In reaching that decision, Judge Scheindlin went through an analysis of class action cases where the primary remedy sought by the plaintiffs was injunctive relief. First, Judge Scheindlin addressed the plaintiffs’ lack of typicality. To do this she looked at a market-share theory of liability. In this case, a majority of the class representatives could identify the responsible gasoline manufacturer, but the ambient well owners would be unable to identify the manufacturer(s) of MTBE that allegedly contaminated their wells. Id. at 337-38.

The court also took issue with the adequacy of representation. In order to be certified as a class, the plaintiffs are required to show that the potential class representatives have no interests that are antagonistic to the proposed class members. In this case, a majority of the class representatives could identify the responsible gasoline manufacturer, but the ambient well owners would be unable to identify the manufacturer(s) of MTBE that allegedly contaminated their wells. Id. at 337-38. Next, the court took issue with the adequacy of representation. In order to be certified as a class, plaintiffs are required to show that the potential class representatives have no interests antagonistic to the proposed class members. In this case, the plaintiffs failed by attempting a claims-splitting approach where they were suing solely for injunctive relief, a proposal that the court pointed out would “haunt the absent class members whose wells may actually have MTBE levels of regulatory significance.” Id. at 338. The court noted that, in seeking only an injunctive relief remedy in a products liability case, the absent class members with personal injury claims or property claims would not be properly represented. Id. at 340.

The court also outlined why, for mass tort cases, class certification should not be granted under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3). The court held that these cases have inherent problems of individualistic causations that would inevitably result in inefficiency and adequacy issues. Id. at 349. MBTE is a prime example where the injuries occurred over many years across four states and were caused directly or indirectly by 20 defendants and innumerable third parties. For these reasons, among others, the court denied the plaintiffs’ motion for class certification.

In re Oxford Health Plans, Inc. Sec. Litig.

In re Oxford Health Plans, Inc. Sec. Litig., 191 F.R.D. 369 (S.D.N.Y. 2000), involved a securities fraud class action. Though lead plaintiffs had already moved for class certification, another plaintiff also moved to be appointed lead plaintiff and certified class representative. Here, Judge Charles L. Brieant held that the proposed class met the prerequisites permitting the case to be maintained as a class action and refused to designate a new class representative or lead plaintiff.

Since this case was a securities class action, the litigation was controlled by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (“PSLRA”). Id. at 372. The class consisted of all persons or entities that purchased Oxford Health Plans, Inc. common stock or call options, or sold Oxford put options, during the class period. Id. In its decision, the court defined the difference between being a lead plaintiff and a class representative. In his reading of the PSLRA, Judge Brieant found that, although the statute provides that a lead plaintiff must otherwise satisfy the requirements of Rule 23, being a lead plaintiff is not the same thing as being a class representative:

Obviously there will be actions brought under the PSLRA by multiple plaintiffs which do not qualify for class action treatment under Rule 23, perhaps for lack of numerosity or for some other reason. Congress is deemed to have understood this and must have intended that the function of lead plaintiff under the PSLRA be different from class representative under Rule 23. There is no requirement found in the plain meaning of the statute that a Lead Plaintiff accept designation of class representative under Rule 23, and the statute does not provide for any specific action by the Court should it turn out after a Lead Plaintiff has been appointed … that Lead Plaintiff should on further examination fail to meet all of the requirements of Rule 23, or simply withdraw his or her expression of willingness to serve as Class Representative

… .

Id. at 378-79. Observing that the PSLRA does not require lead plaintiffs to qualify as class representatives, the court found it appropriate to appoint a group of lead plaintiffs instead of one class representative. Id. at 378. Because of this distinction, the court granted the motion for class certification, but re-opened class discovery so that the defendants could do the appropriate due diligence as to the adequacy of class representatives.

Int’l Business Machines Corp. v. Papermaster

In Int’l Business Machines Corp. v. Papermaster, No. 08-CV-9078 (KMK), 2008 WL 4974508 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 21, 2008), Judge Kenneth M. Karas granted IBM’s motion for a preliminary injunction enjoining defendant Mark D. Papermaster, a former IBM executive, from working for and disclosing confidential information to Apple Inc.

In October 2008, after 26 years of working for IBM, Papermaster entered into an employment agreement with Apple. IBM filed suit, contending that Papermaster’s contract with Apple violated the non-compete agreement that he had signed with IBM. Judge Karas ruled in IBM’s favor. The court found irreparable injury based in part on Papermaster’s access to the “crown jewels” of IBM’s technology, including sensitive information obtained by virtue of Papermaster’s service on two management groups at IBM. Papermaster, 2008 WL 4974508, at *8. Moreover, Judge Karas found that the work for which Apple hired Papermaster would likely draw on his expertise developed at IBM and that such work, especially that involving the iPhone and iPad, would directly compete with IBM. In addition, Papermaster’s non-compete agreement itself acknowledged that IBM would suffer “irreparable harm” if he violated the agreement.

The court also found that the restriction in the non-compete agreement was “limited in time” and that the nature of IBM’s business “requires that the restriction be unlimited in geographic scope.” Papermaster, 2008 WL 4974508, at *11. Furthermore, the court held that the balance of hardships tilted in IBM’s favor because IBM’s most valuable asset was its intellectual property, as to which Mr. Papermaster was a “top expert” at IBM. Id. at *13.

On January 27, 2009, Apple announced that Papermaster would come to Apple as senior vice president of devices hardware engineering and that the litigation with IBM had been settled.

Jones v. Hirschfeld

Paula Jones brought a sexual harassment lawsuit against then President William J. Clinton in 1994. While that decision was under appeal in 1998, New York real estate mogul Abraham Hirschfield publicly offered Jones $1 million to drop the lawsuit. Jones and Hirschfeld then signed an agreement under which Hirschfeld would wire the funds to a trust account held by Jones’s attorneys to be disbursed only once a court order had been entered dismissing with prejudice Jones’s lawsuit against Clinton. They signed the agreement at a press conference on October 31, 1998. Jones thereafter settled the case with Clinton for $850,000, which resulted in its dismissal.

In 2001, while Hirschfeld was in prison for attempting to hire someone to kill his former business partner, Jones filed suit for breach of contract to obtain the $1 million. It was undisputed that Jones had not received the funds as per the agreement, but Hirschfeld argued that his agreement with Jones had been rescinded when she entered into the settlement with Clinton. In Jones v. Hirschfeld, 348 F. Supp. 2d 50 (S.D.N.Y. 2004), Judge Peter K. Leisure held that Jones had rescinded her agreement with Hirschfeld by abandonment and granted Hirschfeld’s two-page motion for summary judgment. Id. at 62-63. Hirschfeld’s memorandum in support of summary judgment relied on a letter from Jones’s attorney to Clinton’s attorney the same day the settlement agreement was signed, which stated that it was the final offer to settle the lawsuit in the amount of $850,000. The letter represented that “the money from Mr. Abraham Hirschfeld is no longer on the table and that there will be no payment from Mr. Hirschfeld as part of the settlement with your client [Clinton].” Id. at 54. Jones’s settlement agreement with Clinton further provided that it was “not subject to any condition, and that the consideration recited herein is the sole consideration for the parties’ agreement to this Stipulation.” Id. at 55.

Judge Leisure ruled that Jones’s “statements of her intentions [in her August 2002 declaration] made almost four years after the fact during the course of litigation, are insufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact in light of her previous unequivocal manifestations of intent to abandon the October 31 agreement.” Id. at 61. Thus, Jones’s claims to the $1 million payout were dismissed.

SR Int’l Bus. Ins. Co. v. World Trade Ctr. Props., LLC

After a trial at which then-Chief Judge Michael B. Mukasey presided, a jury in SR Int’l Bus. Ins. Co. v. World Trade Ctr. Props., LLC, found that nine insurers were bound by agreements that permitted the destruction of the twin towers, 1 World Trade Center and 2 World Trade Center, on September 11, 2001, to be defined as two occurrences, rather than one. The developer of the World Trade Center property had asserted that the applicable insurance policies should be interpreted such that two crashes into two different towers at two different times constituted two separate attacks, entitling the developer to recover up to $7 billion for two occurrences, as opposed to the $3.5 billion for one occurrence. The verdict enabled the developer of the World Trade Center site to seek as much as $1.1 billion in additional coverage.

Previous juries, however, had held that the terrorist attacks constituted one “occurrence” under the terms of certain insurance contracts. The two-phase jury trial presided over by Judge Mukasey determined (i) which insurers were bound to an insurance form that contemplated treating the September 11th attacks as a single occurrence, and (ii) the number of occurrences for each insurer who did not bind to that insurance form. Certain insurers who lost at Phases One and Two of the jury trial appealed the verdict.

The Second Circuit affirmed the judgments entered by the trial court following those two jury verdicts. SR Int’l Bus. Ins. Co. v. World Trade Ctr. Props. LLC, 467 F.3d 107 (2d Cir. 2006). The court concluded that the defined term “occurrence” was not unambiguous. Id. at 138. It also rejected a host of purported evidentiary errors, including the admission of expert testimony and evidence of subjective intent and the exclusion of evidence of custom and usage.

Starr Int’l Co. v. Am. Int’l Group, Inc.

In July 2009, a jury in the Southern District, at which Judge Jed Rakoff presided, decided that Maurice R. Greenberg, the former chief executive officer of American International Group (“AIG”) did not wrongfully seize $4.3 billion in company stock in Starr Int’l Co. v. Am. Int’l Group, Inc., 648 F. Supp. 2d 546 (S.D.N.Y. 2009).

The case revolved around AIG’s retirement plan, which for 35 years was operated by Starr International (“SICO”), AIG’s largest shareholder. In 2005, Greenberg ended the AIG retirement plan and sold its stock for $4.3 billion. Id. at 559. AIG alleged that the stock was in a trust and that Greenberg had no right to sell the stock. Two claims remained for the jury to decide: (i) AIG’s breach-of-trust counterclaim, which alleged that SICO, a company allegedly controlled by Greenberg, held certain AIG stock subject to an express trust for the benefit of AIG and that SICO had breached this trust; and (ii) AIG’s conversion counterclaim, which principally alleged that SICO had converted AIG stock for its own use. Id. at 549. Judge Rakoff determined that a jury would decide the second claim and would render an advisory verdict on the first claim. After a three-week trial, the jury rejected both claims, finding that SICO was not liable on either the breach of trust or conversion claims. Judge Rakoff entered judgment on those claims, accepting the jury’s advisory verdict on AIG’s breach-of-trust counterclaim. Id. at 549.

In re Citigroup Inc. S’holder Derivative Litig.

Judge Sidney H. Stein of the Southern District dismissed without prejudice a multi-billion dollar derivative action brought by Citigroup shareholders—one of the first derivative cases involving the financial crisis of 2008-09 in which a published opinion was rendered. In re Citigroup Inc. S’holder Derivative Litig., No. 07 Civ. 9841, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 75564 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 25, 2009). The plaintiffs alleged that certain current and former officers and directors of Citigroup, its board of directors, and subsidiaries (the “defendants”) had breached their fiduciary duties of care and loyalty by allowing Citigroup to make risky mortgage-related investments, ignoring “red flags” that should have alerted them to the impending financial crisis. Second, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants had failed to inform shareholders of Citigroup’s exposure to risky subprime mortgage-backed securities. Third, the plaintiffs argued that the defendants had breached fiduciary duties and wasted corporate assets by causing Citigroup to repurchase its own stock. Fourth, the plaintiffs contended that the defendants committed securities fraud by failing to disclose the extent of Citigroup’s investment in subprime assets. Fifth, the plaintiffs alleged that some defendants committed insider trading.

Judge Stein dismissed all of these claims, concluding that the allegations in the complaint were insufficient to establish that plaintiffs were excused from the pre-suit demand requirement. Applying the business judgment rule, Judge Stein held that the defendants did not face a substantial likelihood of liability because the plaintiffs did not allege that the defendants acted in bad faith. At most they alleged that the defendants had made bad business decisions. Id. at *21. As for the non-disclosure claims, the court held that the complaint failed to allege with particularity which disclosures were misleading. Id. At *24. The plaintiffs had not alleged that the purported misstatements were made knowingly or in bad faith, or with the substantial involvement and knowledge of the defendants. Id. at *25. The court rejected the securities fraud and insider trading allegations on similar grounds—a lack of particularity in pleading and a failure to allege the involvement of the defendants in the alleged misconduct. Id. at *30-35.

The court also rejected the stock repurchase claims because the plaintiffs had failed to allege that the repurchases were so one-sided that “no reasonable and ordinary business person” would have considered the consideration sufficient. Id. at *28. In addition, the plaintiffs again failed to allege bad faith and alleged at most, according to the court, a bad business decision. Id. at *29.

NYSRA I

The City of New York’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene adopted Health Code § 81.50 (“Regulation 81.50”) to take effect on July 1, 2007. The regulation was to apply to standardized menu items for which calorie content information was made publicly available on or after March 1, 2007. The regulation required restaurants to post the caloric content value for such items on their menus in a typeface at least as large as the name or price of the item, whichever was larger. The City of New York explained that it enacted Regulation 81.50 in response to the obesity epidemic in America—and in New York specifically. The New York State Restaurant Association brought suit alleging that Regulation 81.50 was preempted by federal law and unconstitutional.

In New York State Restaurant Ass’n v. New York City Bd. of Health, 509 F. Supp. 2d 351 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) (“NYSRA I”), Judge Richard J. Holwell ruled in favor of the New York State Restaurant Association, finding that Regulation 81.50 was preempted by the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, PL 101–535, November 8, 1990, 104 Stat 2353 (“NLEA”). Section 343(r) of the NLEA requires a purveyor to use regulated terms if it labels its food by specifying the levels of any nutrient. Section 343(r) applies only where a purveyor voluntarily chooses to make such a claim. The NLEA expressly preempts states from regulating voluntary claims under Section 403(r), unless the states’ requirements are identical to the federal requirements. See 21 U.S.C. § 343-1(a)(5). Judge Holwell held that, because Regulation 81.50’s requirements applied only if a restaurant chooses to make calorie content information available, the provisions of Section 343(r) were implicated and, thus, preempted by Section 343-1(a)(5). NYSRA I at 363. The City of New York was therefore permanently enjoined from enforcing Regulation 80.51.

NYSRA II

The City of New York did not appeal Judge Holwell’s ruling in NYSRA I and instead sought to cure Regulation 81.50’s deficiencies. The revamped Regulation 81.50 required mandatory compliance by restaurants that were part of a national chain of 15 or more food service establishments with standardized menu items. Judge Holwell revisited the preemption issue with respect to the revised Regulation 81.50 in New York State Restaurant Ass’n v. New York City Bd. of Health, No. 08 Civ. 1000 (RJH), 2008 WL 1752455 (S.D.N.Y. April 16, 2008) (“NYSRA II”). He ruled that, because compliance with the regulation was now mandatory, preemption would be governed by NLEA § 343-1(a)(4), which made expressly clear that the federal statute did not apply to food served in restaurants. Id. at *5. Accordingly, the revised Regulation 81.50 was not preempted.

Judge Holwell further dismissed NYSRA’s argument that Regulation 81.50 violated a First Amendment right to be free from compelled speech. Judge Holwell distinguished “the mandatory disclosure of factual and uncontroversial information” from “the compelled endorsement of a viewpoint.” Id at *9 (internal citations omitted). The court further ruled that Regulation 81.50 was reasonably related to the City of New York’s interest in reducing obesity. Id. at *12. Accordingly, the court declined to enter a preliminary injunction against the revised regulation.

In re Fosamax Products Liability Litigation

More than 900 cases were consolidated as part of the multidistrict litigation in In re Fosamax Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 06 MD 1789. Plaintiffs sued Merck & Co., Inc. (“Merck”) alleging that its osteoporosis drug Fosamax caused osteonecrosis of the jaw (“ONJ”), a condition that results in exposure of nonvital bone tissue that can lead to jawbone disintegration. Judge John F. Keenan presided over issues common to the consolidated cases.

Shirley Boles, a 71-year-old Florida resident and former deputy sheriff, alleged that taking Fosamax for almost ten years resulted in ONJ and stunted bone healing that caused her to develop ongoing infections following a tooth extraction. Boles’s case was one of several selected as bellwethers in the Fosamax litigation. The parties hotly disputed the point at which Merck should have warned patients about Fosamax’s potential risks and whether that duty arose prior to when Boles developed ONJ. In In re Fosamax Products Liability Litigation, 647 F. Supp. 2d 265, 275 (S.D.N.Y. 2009), Judge Keenan held that the adequacy of the warning would be assessed at the time of the injury and the time at which the product left the manufacturer’s control. After Boles’s first trial ended in a hung jury, the retrial resulted in an $8 million verdict for the plaintiff. Judge Keenan subsequently ordered a remittitur of the verdict to $1.5 million in In re Fosamax Prods. Liab. Litig., 742 F. Supp. 2d 460, 486 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). Two other cases, Flemings v. Merck & Co., Inc., 06 Civ. 7631 (JFK) and Greene v. Merck & Co. Inc., 06 Civ. 5088 (JFK), were also chosen as initial bellwethers along with Boles’s case. Both Flemings and Greene resulted in verdicts in favor of defendant Merck.

United States v. Gotti

John A. Gotti III, a/k/a Junior Gotti, son of convicted Gambino boss John J. Gotti, Jr., was the target of two federal indictments. The first indictment was filed in 2004 and charged him with 11 counts of racketeering as well as several other crimes. One of those counts alleged a plot to kill Curtis Sliwa, radio host and founder of the Guardian Angels, for denouncing Gotti as “Public Enemy No. 1.” The second indictment included charges under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act and murder conspiracy charges derived from a drug trafficking ring he ran, along with the murders of two drug ring associates. This indictment was first filed in Florida in 2008 but later moved to New York and tried in the Southern District.

Though Gotti failed to have some counts of the first indictment dismissed because he argued they were covered under a previous plea deal in the late 1990s, the federal prosecutors still did not have an easy time proving their case. The first three trials all ended in hung juries. These trials were dramatic and included press demands for greater information access, jurors questioning prosecution witnesses’ credibility, presiding Judge Kevin Castel dismissing two bickering jurors on November 4, 2009, and angry outbursts from Gotti’s mother about her son being “railroaded” like his father by the prosecutors. Nonetheless, Gotti continued to deny the charges, saying he left the mob long before the crimes in question occurred, which enabled him to avoid conviction in the first three trials. By December 1, 2009, the fourth trial also ended in a hung jury. Not long afterward, U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara issued a nolle prosequi order on January 13, 2010, declaring that no further prosecutions of Gotti will be made on these charges.

Gotti’s uncle, Peter Gotti, was convicted on charges of conspiring to murder, construction industry extortion, and racketeering in a 2004 trial presided over by Judge Richard C. Casey. The conviction was upheld by the Second Circuit in 2007. United States v. Matera, 489 F.3d 115 (2d Cir. 2007). At the time of his conviction, Gotti was already serving nine years in prison for a conviction on separate money-laundering and racketeering charges. Peter Gotti was convicted for plotting to kill Salvatore Gravano, known to the Gambino crime family as Sammy the Bull, for Gravano’s cooperation with authorities in the 1992 murder conviction of John J. Gotti, Jr.

United States v. Muse

Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse, a Somali teenager, was tried for federal hijacking and kidnapping in 2009 for a piracy incident involving a U.S. container ship, the Maersk Alabama, in international waters off the coast of Somalia in the Indian Ocean. Muse and a gang of three other gun-toting pirates boarded the ship on April 8, 2009, taking Captain Richard Phillips hostage on one of the Alabama’s lifeboats. Navy SEAL snipers killed Muse’s three cohorts on April 12 and rescued Captain Phillips, leaving Muse to be taken into custody by the U.S. Navy.

Muse later was taken into FBI custody and flown to the Southern District on April 20, 2009. He was the first person to be tried for piracy in an American court in more than 100 years. According to a report in The Guardian, U.S. authorities decided to bring Muse to New York because he was arrested in international waters and the FBI in New York had acquired a specialty in dealing with East African legal affairs.

Magistrate Judge Andrew J. Peck first determined in a closed hearing on April 21, 2009 that Muse was at least 18 years old, allowing him to be tried as an adult. This ruling came after his parents claimed that he was 16, which would have placed limits on his trial and sentence. The next month, on May 19, a federal grand jury returned a ten-count indictment against Muse, including the piracy charge and possession of a firearm. However, Muse pled guilty to felony charges of hijacking, kidnapping, and hostage-taking one day earlier.

On February 16, 2011, Chief Judge Loretta A. Preska sentenced Muse to almost 34 years in prison for his participation in the hijacking of the Maersk Alabama and hostage taking and for his hijacking of two other vessels earlier in 2009. Regarding the sentencing, FBI Assistant Director Janice K. Fedarcyk said, “The stiff sentence handed down today sends a clear message to others who would interfere with American vessels or do harm to Americans on the high seas: Whatever seas you ply, you are not beyond the reach of American justice, and you will be held accountable for your actions.”

U.S. v. Stewart

On March 5, 2004, a jury convicted celebrity business magnate and television personality Martha Stewart of conspiracy, making false statements to investigators in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001, and obstruction of an agency proceeding. The statements at issue were made during an investigation to determine whether Stewart had traded on inside information when she sold shares of stock in ImClone Systems, Inc. (“ImClone”), whose CEO was a close friend of her Merrill Lynch stockbroker, Peter Bacanovic. In the same trial, Bacanovic also was convicted. Stewart sold her almost 4,000 shares of ImClone stock two days after the Food and Drug Administration had rejected ImClone’s application for approval of a cancer-fighting medication called Erbitux. Stewart’s shares were sold one day prior to ImClone’s public disclosure of the rejection.

Following their convictions, Stewart and Bacanovic moved for a new trial pursuant to Fed. R. Crim. P. 33, claiming that one of the jurors deliberately concealed material information in his jury questionnaire. Judge Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum denied the motion for retrial in the absence of that juror’s bias, noting that “the law is clear that lack of candor, in the absence of evidence of bias, does not undermine the fairness of defendant’s trial.” U.S. v. Stewart, 317 F. Supp. 2d 432, 443 (S.D.N.Y. 2004).

Stewart and Bacanovic brought a further motion for retrial after the government indicted one of its trial experts, alleging that he committed perjury in his trial testimony. Judge Cedarbaum again denied Stewart’s request for a new trial, ruling that the false testimony had not influenced the jury and that “Stewart was convicted on the testimony of Bacanovic’s assistant, her own assistant, and her best friend.” U.S. v. Stewart, 323 F. Supp. 2d 606, 622 (S.D.N.Y. 2004).

Both opinions were upheld on appeal in United States v. Stewart, 433 F.3d 273, 288 (2d Cir. 2006). Stewart ultimately received a sentence that included a five-month term in federal prison, five months of house arrest and two years of probation.

Any discussion of E-Discovery in the Southern District must start with Judge Shira A. Scheindlin’s decisions in the Zubulake case, as these five decisions shaped E-Discovery in the decade and became well known throughout the country. Below is a brief summary of the Zubulake Five:

Zubulake I, II, III

In Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 217 F.R.D. 309 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“Zubulake I”), a plaintiff in a gender-discrimination suit requested that the defendant employer produce “[a]ll documents concerning any communication by or between UBS employees concerning the plaintiff.” After defendant’s production was demonstrably lacking, plaintiff requested that defendant produce email from archival media and other backup media. Claiming undue burden and expense, the defendant urged the court to shift the cost of production to the plaintiff. The court modified the eight-factor cost-shifting test in Rowe Entm’t, Inc. v. William Morris Agency, Inc., 205 F.R.D. 421 (S.D.N.Y. 2002), explaining that application of the Rowe factors may unfairly shift costs away from large defendants, particularly in high-stakes litigation. Using a modified seven-factor test, the court ordered the defendant to produce, at its own expense, all responsive email existing on its active servers and on certain backup media. The court left open the question of cost-shifting for after the contents of defendant’s archival and backup media were reviewed and the defendant’s costs were quantified. See also Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 230 F.R.D. 290 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (Zubulake II); Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 216 F.R.D. 280 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (Zubulake III) (discussing cost-shifting).

Zubulake IV

In Zubulake IV, Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 220 F.R.D. 212 (S.D.N.Y. 2003), the court considered spoliation of evidence. In the restoration effort resulting from previous Zubulake decisions, the parties discovered that certain backup data was missing and that emails had been deleted. The plaintiff moved for evidentiary and monetary sanctions. Despite finding the requisite culpability to order severe sanctions, the court found that plaintiff could not demonstrate that the lost evidence would have supported her claims and, accordingly, did not give an adverse inference instruction to the jury. 220 F.R.D. at 221. Instead, the court ordered the defendant to bear plaintiff’s costs for re-deposing certain witnesses for the limited purpose of inquiring into the destruction of electronic evidence and any newly discovered emails.

Zubulake V

In Zubulake V, Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 229 F.R.D. 422 (S.D.N.Y. 2004), the court revisited its earlier sanctions determinations based upon new evidence that the employer had willfully deleted relevant emails despite contrary court orders. The court granted the motion for sanctions and also ordered the employer to pay certain costs. The court held defense counsel partly to blame for the document destruction because it had failed in its duty to locate relevant information, to preserve that information, and to timely produce that information. In addressing the role of counsel in litigation generally, the court stated, “Counsel must take affirmative steps to monitor compliance so that all sources of discoverable information are identified and searched.” Id. at 432. Specifically, the court concluded that attorneys are obligated to ensure that all relevant documents are discovered, retained, and produced. Additionally, the court declared that litigators must guarantee that identified relevant documents are preserved by placing a “litigation hold” on the documents, communicating the need to preserve them, and arranging for safeguarding of relevant and accessible archival media. Id. at 431-32.

The Zubulake decisions have been adopted in New York State courts as well. In early 2012, the Appellate Division, First Department, twice held that the costs of searching and producing documents and electronically stored information in response to discovery requests falls initially on the party responding to the requests—and that courts may later shift that cost at their discretion. This standard was applied in Voom HD Holdings v. EchoStar Satellite LLC, 600292/08, 2012 N.Y. App. Div. LEXIS 559 (1st Dep’t Jan. 31, 2012) and again in U.S. Bank Nat’l Ass’n v. Green Point Mortgage Funding Inc., 600352/09, 2012 N.Y. App. Div. LEXIS 1487 (1st Dep’t Feb. 28, 2012). In the latter opinion, Justice Rolando T. Acosta wrote that the court was “persuaded that Zubulake should be the rule in this Department.” Id. At *2.

Pension Committee of Univ. of Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities, LLC